Henri Matisse (1869 - 1954) 8 Phases of arts

94

He was the most outstanding colorist of the 20th century, with innovations compared to those of Picasso.

Matisse was also counted among the famous French and Expressionist artists.

He was a leading pillar of Fauvism and was recognized as the head of the French movement.

Henri Émile Benoît Matisse (French: [ɑ̃ʁi emil bənwa matis]; 31 December 1869 – 3 November 1954) was a French visual artist, known for both his use of colour and his fluid and original draughtsmanship. He was a draughtsman, printmaker, and sculptor, but is known primarily as a painter.[1] Matisse is commonly regarded, along with Pablo Picasso, as one of the artists who best helped to define the revolutionary developments in the visual arts throughout the opening decades of the twentieth century, responsible for significant developments in painting and sculpture.[2][3][4][5] The intense colourism of the works he painted between 1900 and 1905 brought him notoriety as one of the Fauves (French for "wild beasts"). Many of his finest works were created in the decade or so after 1906, when he developed a rigorous style that emphasized flattened forms and decorative pattern. In 1917, he relocated to a suburb of Nice on the French Riviera, and the more relaxed style of his work during the 1920s gained him critical acclaim as an upholder of the classical tradition in French painting.[6] After 1930, he adopted a bolder simplification of form. When ill health in his final years prevented him from painting, he created an important body of work in the medium of cut paper collage.

Early Paintings

Matisse - Fruit and Coffeepot (1898)

Study of a Nude by Henri Matisse, 1899

Henri Matisse, 1899, Still Life with Compote, Apples and Oranges, oil on canvas, 46.4 x 55.6 cm, The Cone Collection, Baltimore Museum of Art

Matisse began painting in 1889, near the edge of 20. Though he started relatively late in life (studying to be a lawyer first) and only by chance when his mother bought him a set of painting supplies to keep himself occupied while bedridden, recovering from appendicitis, Matisse soon became completely enamored with art. He emptied his bank accounts on one occasion to buy art from the artists he admired. The early works show Matisse was inspired by many — Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cezanne and Rodin — though if there was one painter above all who would claim the lion’s share of his devotion, it would be Cezanne. That artist’s color sensibilities and compositional skill would inspire Matisse extensively over the years. Many of the early paintings exhibit a Divisionist style, with unblended patches of color apparent on the canvas, leaving the color “mixing” to the eye. The work is also focused largely on form and is somewhat reserved and conventional in color and subject matter.

Growing Access and Influence

The Fauvist Period

Matisse is often regarded as the leader of Fauvism, an avant-garde movement that flourished in France in the early 20th century. Fauvists were known for their radical use of colour, using it to express emotion rather than merely to depict the world realistically. This use of non-naturalistic and bold colours was considered groundbreaking, and Matisse's work in this period had a significant impact on the course of modern art.

Henri Matisse, The Luxembourg Gardens (1901), oil on canvas, 59.5 x 81.5 cm, State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia

Henri Matisse, Dishes and Fruit (1901), oil on canvas, 51 x 61.5 cm Source State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia

It lasted a bit more than a decade and its heydays were from 1904-1908 with three exhibitions that put its leaders, one of whom was Matisse, on the map. The Fauvist style was known for its wild, uncontrolled color that had no basis in nature. The application of the paint was thought to be raw and unrefined, the work of “wild beasts,” which is where the term Fauvism derives.

1904-05 Luxe, Calme, et Volupte

The title of this painting is taken from the refrain of Charles Baudelaire's poem, Invitation to a Voyage (1857), in which a man invites his lover to travel with him to paradise. The landscape is likely based on the view from Paul Signac's house in Saint-Tropez, where Matisse was vacationing. Most of the women are nude (in the manner of a traditional classical idyll), but one woman - thought to represent the painter's wife - wears contemporary dress. This is Matisse's only major painting in the Neo-Impressionist mode, and its technique was inspired by the Pointillism of Paul Signac and Georges Seurat. He differs from the approach of those painters, however, in the way in which he outlines figures to give them emphasis.

Luxe, Calme et Volupté ("Luxury, Calm and Pleasure") by Henri Matisse, 1904. Oil on canvas, 98 x 118.5 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. This painting was first shown at the Salon des Indépendants, 1905

Les toits de Collioure, 1905

Open Window, Collioure by Henri Matisse, 1905. Oil on canvas, 55.25 x 46.04 cm, 21 3/4 x 18 1/8 in. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.7.

Woman With a Hat by Henri Matisse, 1905

1905: The Woman with a Hat

Matisse attacked conventional portraiture with this image of his wife. Amelie's pose and dress are typical for the day, but Matisse roughly applied brilliant color across her face, hat, dress, and even the background. This shocked his contemporaries when he sent the picture to the 1905 Salon d'Automne. Leo Stein called it, "the nastiest smear of paint I had ever seen," yet he and Gertrude bought it for the importance they knew it would have to modern painting.

Oil on canvas - The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

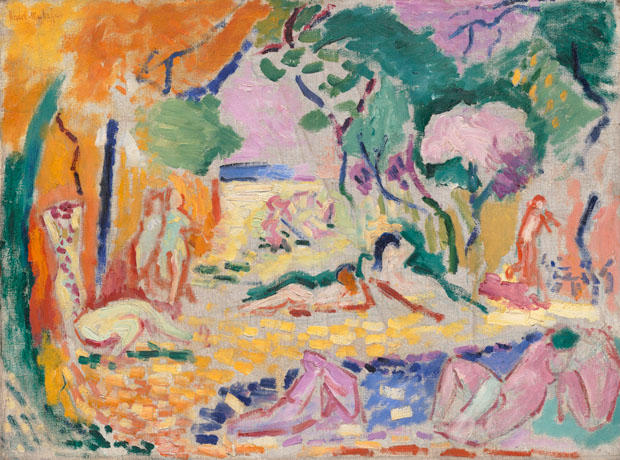

Le bonheur de vivre, Henri Matisse, 1905-1906, Oil on canvas, 176.5 x 240.7 cm (69 1/2 x 94 3/4 in.). In the collection of the Barnes Foundation.

1905-06: Joy of Life (Le Bonheur de Vivre)

During his Fauve years Matisse often painted landscapes in the south of France during the summer and worked up ideas developed there into larger compositions upon his return to Paris. Joy of Life, the second of his important imaginary compositions, is typical of these. He used a landscape he had painted in Collioure to provide the setting for the idyll, but it is also influenced by ideas drawn from Watteau, Poussin, Japanese woodcuts, Persian miniatures, and 19th-century Orientalist images of harems. The scene is made up of independent motifs arranged to form a complete composition. The massive painting and its shocking colors received mixed reviews at the Salon des Indépendants. Critics noted its new style -- broad fields of color and linear figures, a clear rejection of Paul Signac's celebrated Pointillism.

In April 1906, Matisse met Pablo Picasso, who would become a lifelong friend and foil when it came to art. The two were often compared. In contrast to Picasso though, Matisse more often painted from life and his figures were painted in more fully realized settings. Matisse came to teach at the Académie Matisse in Paris, funded by wealthy friends, from 1907-11. He also became close with Gertrude Stein and her circle. Of Matisse’s work on view at her weekly salon gatherings at 27 rue de Fleurus, Gertrude Stein said: “More and more frequently, people began visiting to see the Matisse paintings—and the Cézannes: Matisse brought people, everybody brought somebody, and they came at any time and it began to be a nuisance, and it was in this way that Saturday evenings began.”

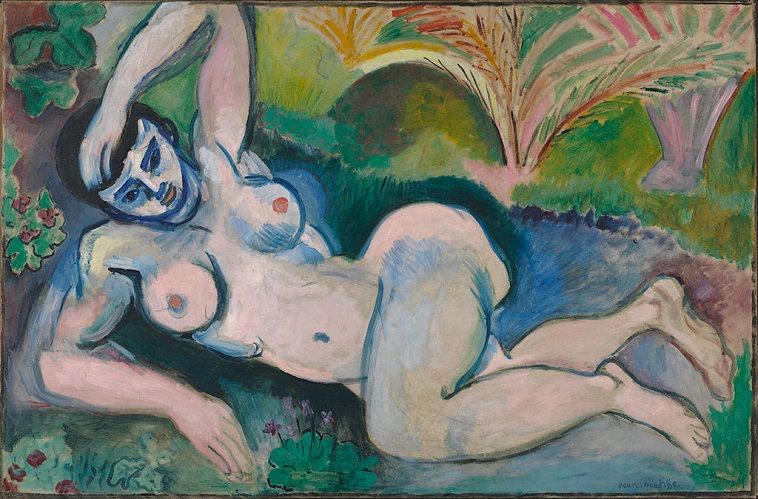

1907: Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra)

Matisse was working on a sculpture, Reclining Nude I, when he accidentally damaged the piece. Before repairing it, he painted it in blue against a background of palm fronds. The nude is hard and angular, both a tribute to Cézanne and to the sculpture Matisse saw in Algeria. She is also a deliberate response to nudes seen in the Paris Salon - ugly and hard rather than soft and pretty. This was the last Matisse painting bought by Leo and Gertrude Stein.

Oil on canvas - The Baltimore Museum of Art, The Cone Collection

Henri Matisse, La danse (first version) 1909, oil on canvas, 8' 6 1/2" x 12' 9 1/2" (259.7 x 390.1 cm). Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller in honor of Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Museum of Modern Art, New York City, New York

Matisse's Return to a More Balanced Approach

In the decade that followed the Fauvist period, Matisse began to balance his audacious use of colour with a renewed interest in drawing and structure. His works became more balanced, with compositions carefully constructed through colour and form. A sense of harmony and serenity characterised pieces such as ‘The Red Room (Harmony in Red)’ (1908) and ‘The Dance’ (1910).

Highest Highs and Lows

Matisse’s work in the 1910s is all about bright, expressive color and planes of color with a particular attention to line. When Fauvism fades, he’s well on his way, continuing to absorb the visual language of Primitivism and African art, and travelling far and wide — from Algiers to Spain and Morocco. In many quarters, his art is well received. Art critic Guillaume Apollinaire calls his work “eminently reasonable” and he is part of the major artistic movement taking place in Paris during the time. Many of his most famous works are produced during this era. But simultaneous to painting masterpieces like La Danse, Matisse is also forced to deal with critical scorn, difficulty selling his work and, at the Armory Show in Chicago in 1913, having his painting, Nu bleu, burned in protest.

Henri Matisse, Music (1910), oil on canvas, 260 x 389 cm Source State Hermitage Museum , Saint Petersburg, Russia

Henri Matisse, 1910-12, Les Capucines (Nasturtiums with The Dance II), oil on canvas, 193 x 114 cm, Pushkin Museum, Moscow

1915-16: The Moroccans

Matisse planned this picture as early as 1913, and it recalls visits made to Morocco around this time. A figure sits on the right with a back to us, fruit lies in the left foreground, and a mosque rises in the background beyond a terrace. Matisse said that he occasionally used black in his pictures in order to simplify the composition, though here it undoubtedly also recalls the stark shadows produced by the strong sunshine in the region. Like Bathers by a River (1917), The Moroccans was significantly influenced by Picasso's Cubism, and some have even compared it to Picasso's Three Musicians (1921). Although it employs the same brilliant color as much of Matisse's work, its use of abstract motifs and rigid diagrammatic composition is unusual, and has attracted considerable speculation. Rather than use the scene as an opportunity for decoration, it is as if Matisse has tried to find the means to chart and map it.

Return to Order

In 1917, Matisse moved his household to Cimiez, a suburb of Nice on the French Rivera. His work of the decade or so following this relocation shows a relaxation and softening of his approach. This "return to order" is characteristic of much post-World War I art, and can be compared with the neoclassicism of Picasso and Stravinsky as well as the return to traditionalism of Derain.

Like many post-World War I artists, Matisse pulls back on extremism. He found comfort, it seems, in more relaxed, softer subjects and depictions. Some critics called the works of this period decorative and shallow, but Matisse was not alone — this pulling back was a phenomenon seen among many artists of this period including Picasso and Stravinsky.

After Paris

The Dance Continues

In the late 1920s, Matisse once again engaged in active collaborations with other artists. He worked with not only Frenchmen, Dutch, Germans, and Spaniards, but also a few Americans and recent American immigrants.

In the 1920s, Matisse reengaged with the art world at large, create many works in collaboration with artists worldwide. The 1930s brought a renewed commitment and boldness to his work. Large Reclining Nude was created and indicates where the next big thing for Matisse is headed: simplified forms and cutouts.

The Nice Period and Later Work

By the 1920s, Matisse entered his 'Nice period,' named after the city in the south of France where he worked. The atmosphere and light of the Mediterranean influenced his palette to become softer and lighter. This period lasted roughly until 1930, though Matisse continued to visit Nice throughout his life. He began creating images of interiors, still lifes, and many depictions of reclining or seated odalisques - women in Turkish dress or sometimes semi-nude.

After 1930, a new vigor and bolder simplification appeared in his work. American art collector Albert C. Barnes convinced Matisse to produce a large mural for the Barnes Foundation, The Dance II, which was completed in 1932; the Foundation owns several dozen other Matisse paintings. This move toward simplification and a foreshadowing of the cut-out technique is also evident in his painting Large Reclining Nude (1935). Matisse worked on this painting for several months and documented the progress with a series of 22 photographs, which he sent to Etta Cone.

Oil on canvas - Barnes Foundation, Merion, Pennsylvania

1932: The Dance II

Albert Barnes, a doctor and art lover, commissioned Matisse in 1931 to paint a mural for the main hall of his gallery housing works by Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, and others. Matisse created a maquette for the mural out of cut paper, which he could rearrange as he determined the composition. However, the finished work was too small for the space due to being given incorrect measurements. Rather than add a decorative border, Matisse decided to recompose the entire piece, resulting in a dynamic composition, in which bodies seem to leap across abstracted space of pink and blue fields.

Occupied Art During World War II years

Matisse could have fled France during the onset of World War II but chose to stay and as a non-Jewish citizen he was able to do so relatively safely. “It seemed to me as if I would be deserting,” he wrote to his son, Pierre, in September 1940. “If everyone who has any value leaves France, what remains of France?” Matisse continued to make art and was, surprisingly, able to display his work during this time. He also worked as a graphic artist, creating black and white book illustrations and some hundred lithographs.

Matisse's wife Amélie, who suspected that he was having an affair with her young Russian emigre companion, Lydia Delectorskaya, ended their 41-year marriage in July 1939, dividing their possessions equally between them. Delectorskaya attempted suicide by shooting herself in the chest; remarkably, she survived with no serious after-effects, and returned to Matisse and worked with him for the rest of his life, running his household, paying the bills, typing his correspondence, keeping meticulous records, assisting in the studio, and coordinating his business affairs.[50]

Matisse was visiting Paris when the Nazis invaded France in June 1940, but managed to make his way back to Nice. His son, Pierre, by then a gallery owner in New York, begged him to flee while he could. Matisse was about to depart for Brazil to escape the occupation of France but changed his mind and remained in Nice, in Vichy France. "It seemed to me as if I would be deserting," he wrote Pierre in September 1940. "If everyone who has any value leaves France, what remains of France?". Although he was never a member of the resistance, it became a point of pride to the occupied French that one of their most acclaimed artists chose to stay.[51]

While the Nazis occupied France from 1940 to 1944, they were more lenient in their attacks on "degenerate art" in Paris than they were in the German-speaking nations under their military dictatorship. Matisse was allowed to exhibit, along with other former Fauves and Cubists whom Hitler had initially claimed to despise, though without any Jewish artists, all of whose works had been purged from all French museums and galleries; any French artists exhibiting in France had to sign an oath assuring their "Aryan" status, including Matisse.[52] He also worked as a graphic artist and produced black-and-white illustrations for several books and over one hundred original lithographs at the Mourlot Studios in Paris.

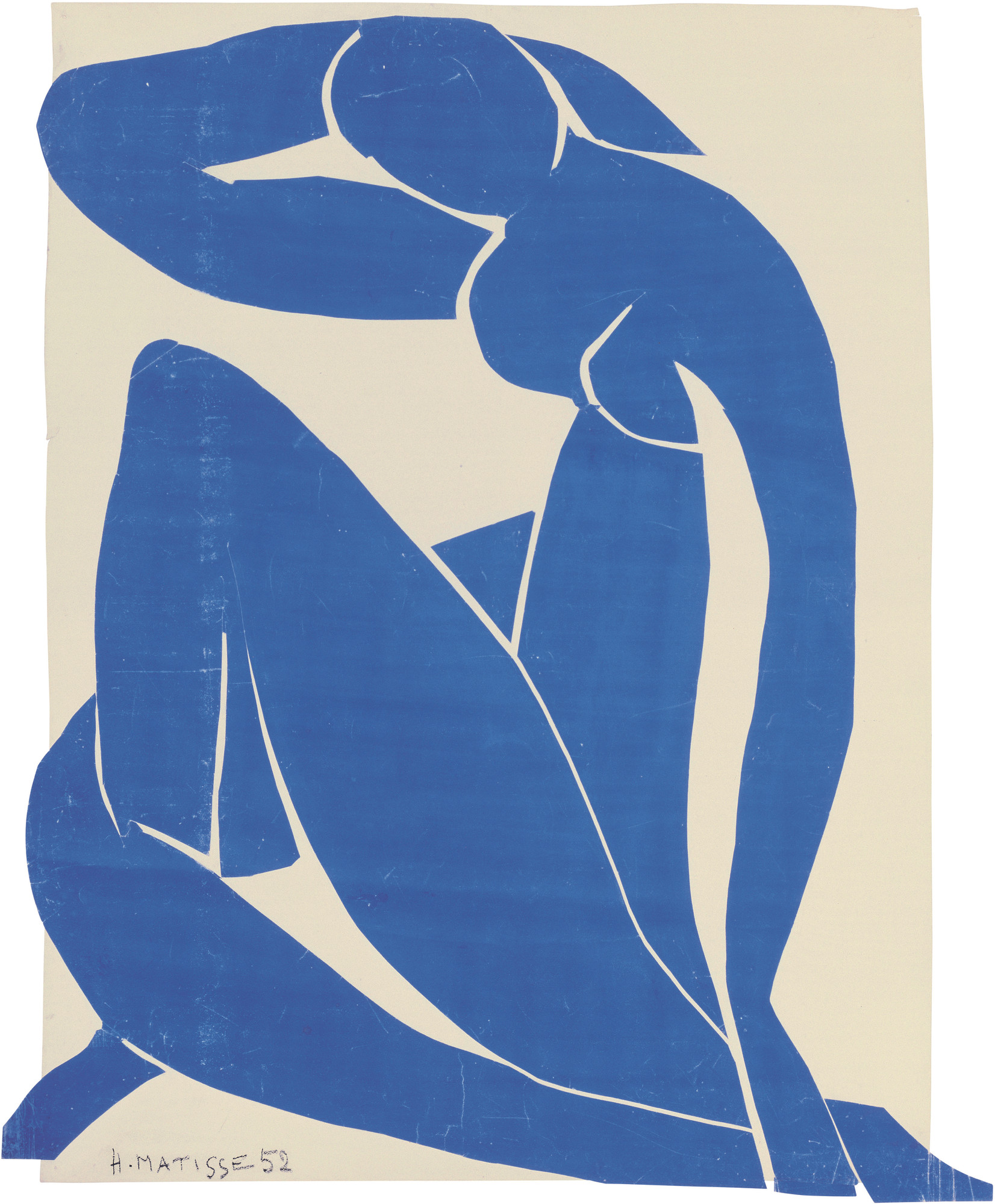

1952 Blue Nude II

Matisse completed a series of four blue nudes in 1952, each in his favorite pose of entwined legs and raised arm. Matisse had been making cut-outs for eleven years, but had not yet seriously attempted to portray the human figure. In preparation for these works, Matisse filled a notebook with studies. He then created a figure that is abstracted and simplified, a symbol for the nude, before incorporating the nude into his large-scale murals.

Gouache-painted paper cut-outs - Private Collection

The Cut-Outs: Matisse's Final Artistic Phase

Matisse's final artistic transformation came when ill health prevented him from painting. In the 1940s, he began to work with painted paper cut-outs, creating compositions of great energy and fluidity. His cut-outs, such as 'The Snail' and 'Blue Nudes,' were characterised by an innovative use of colour, form, and space. This period represented not only a new medium but also a culmination of Matisse’s lifelong exploration of colour and form.

The Cutouts

In 1941, Matisse was diagnosed with duodenal cancer. The surgery, while successful, resulted in serious complications from which he nearly died. Being bedridden for three months resulted in his developing a new art form using paper and scissors.

In the early 1940s, after surgery, Matisse again discovered a love for an art form while convalescing. This time, with paper and scissors, creating cutouts and collages that would eventually replace painting completely for the artist. These started on the small scale but eventually came to occupy entire rooms as full-size cutout murals. Matisse finished his last painting in 1951 and the cutouts were the last artworks he ever made.

Diagnosed with abdominal cancer in 1941, Matisse underwent surgery that left him reliant on a wheelchair and often bedbound. Painting and sculpture had become physical challenges, so he turned to a new type of medium. With the help of his assistants, he began creating cut paper collages, or decoupage. He would cut sheets of paper, pre-painted with gouache by his assistants, into shapes of varying colours and sizes, and arrange them to form lively compositions. Initially, these pieces were modest in size, but eventually transformed into murals or room-sized works. The result was a distinct and dimensional complexity—an art form that was not quite painting, but not quite sculpture.[58][59] He called the last fourteen years of his life "une seconde vie", meaning his second life. When talking about his work, Matisse mentioned that, while his mobility was limited, he could wander through gardens in the form of his artwork.[60][61]

Although the paper cut-out was Matisse's major medium in the final decade of his life, his first recorded use of the technique was in 1919 during the design of decor for the Le chant du rossignol, an opera composed by Igor Stravinsky.[59] Albert C. Barnes arranged for cardboard templates to be made of the unusual dimensions of the walls onto which Matisse, in his studio in Nice, fixed the composition of painted paper shapes. Another group of cut-outs were made between 1937 and 1938, while Matisse was working on the stage sets and costumes for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. However, it was only after his operation that, bedridden, Matisse began to develop the cut-out technique as its own form, rather than its prior utilitarian origin.[62][63]

He moved to the hilltop of Vence, France in 1943, where he produced his first major cut-out project for his artist's book titled Jazz. However, these cut-outs were conceived as designs for stencil prints to be looked at in the book, rather than as independent pictorial works. At this point, Matisse still thought of the cut-outs as separate from his principal art form. His new understanding of this medium unfolds with the 1946 introduction for Jazz. After summarizing his career, Matisse refers to the possibilities the cut-out technique offers, insisting "An artist must never be a prisoner of himself, prisoner of a style, prisoner of a reputation, prisoner of success…"[62]

The number of independently conceived cut-outs steadily increased following Jazz, and eventually led to the creation of mural-size works, such as Oceania the Sky and Oceania the Sea of 1946. Under Matisse's direction, Lydia Delectorskaya, his studio assistant, loosely pinned the silhouettes of birds, fish, and marine vegetation directly onto the walls of the room. The two Oceania pieces, his first cut-outs of this scale, evoked a trip to Tahiti he made years before.[64]

In May 1954, his cut out The Sheaf was exhibited at the Salon de Mai and met with success.[65] The artwork was a commission for American collectors Mr and Mrs Brody and the cut out was then adapted to a ceramic for their house in Los Angeles. It is now located in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.[66]

Chapel and museum

[edit]In 1948, Matisse began to prepare designs for the Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence, which allowed him to expand this technique within a truly decorative context. The experience of designing the chapel windows, chasubles, and tabernacle door—all planned using the cut-out method—had the effect of consolidating the medium as his primary focus. Finishing his last painting in 1951 (and final sculpture the year before), Matisse utilized the paper cut-out as his sole medium for expression up until his death.[67]

This project was the result of the close friendship between Matisse and Bourgeois, now Sister Jacques-Marie, despite him being an atheist.[68][69] They had met again in Vence and started the collaboration, a story related in her 1992 book Henri Matisse: La Chapelle de Vence and in the 2003 documentary "A Model for Matisse".[70]

In 1952, he established a museum dedicated to his work, the Matisse Museum in Le Cateau, and this museum is now the third-largest collection of Matisse works in France.

According to David Rockefeller, Matisse's final work was the design for a stained-glass window installed at the Union Church of Pocantico Hills near the Rockefeller estate north of New York City. "It was his final artistic creation; the maquette was on the wall of his bedroom when he died in November of 1954", Rockefeller writes. Installation was completed in 1956.[71]

Death

Matisse died of a heart attack at the age of 84 on 3 November 1954. He is buried in the cemetery of the Monastère Notre Dame de Cimiez, in the Cimiez neighbourhood of Nice.

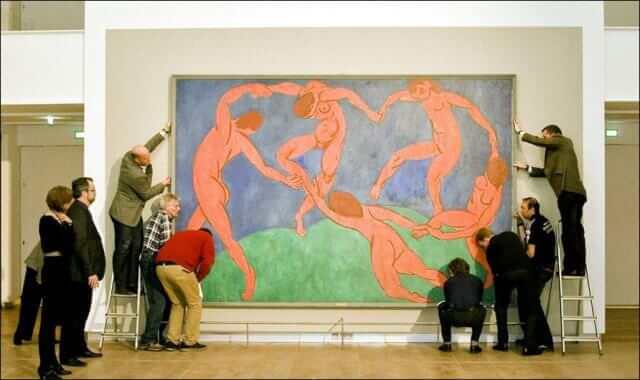

The Dance

Dance (La Danse) is a painting made by Henri Matisse in 1910, at the request of Russian businessman and art collector Sergei Shchukin, who bequeathed the large decorative panel to the Hermitage Museum, in Saint Petersburg. The composition of dancing figures is commonly recognized as "a key point of (Matisse's) career and in the development of modern painting". A preliminary version of the work, sketched by Matisse in 1909 as a study for the work, resides at MoMA in New York, where it has been labeled Dance (I). La Danse was first exhibited at the Salon d'Automne of 1910 (1 October – 8 November), Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées, Paris.

There were two reasons why he created the dance painting:

First, Matisse once said that he wanted to create a piece of work that’d leave a soothing effect on the inner soul of the viewer. Just like a smooth and nice couch.

His viewers would feel contentment after witnessing his work.

The second reason was Sergei Shchukin, a Russian businessman and art patron who was also a close admirer of Henri’s work.

During the year 1910, he commissioned Matisse two large decorative panels for his Trubetskoy Palace.

Matisse borrowed the motif from the back of the 1905-06 painting Bonheur de Vivre, although he has removed one dancer.

The Dance Inital Study

In Dance I, the figures express the light pleasure and joy that was so much a part of the earlier Fauve masterpiece. The figures are drawn loosely, with almost no interior definition. Matisse has been careful to allow this break only where it overlaps the knee so as not to interrupt the continuity of the color. Why do this? The part is often interpreted in two ways, as a source of tension that requires resolution or, as an invitation to us the viewer to join in, after all, the break is at the point closest to our position.

The image you notice above is the first “Dance” by Henri Matisse.

Skin-colored humans dancing while holding hands in a circle—the details are the simplest one can ever look for, don’t you think? This famous dance artwork admires the artist, who once defined it as an “overwhelming peak of brilliance.”

Do you know that the unclothed figures were never a call from Shchukin?

Sergei (the man who commissioned Henri) requested specifically for dancers depicted in costumes.

But Matisse had other thoughts already running through his mind.

It was his decision to represent the dancers in an undressed manner in order to illuminate a sensational view for the audience. But you know that subjects like these were always brought into the light of criticism.

Henri was accused of suffering from a mental health issue due to the depiction of such a disgraceful picture.

However, it didn’t stop the painting from reaching out to people.

And as we all know, it became a massive success!

There and in the initial study (top), all five figures are female. Yet no-one seems to have noted the obvious: that Matisse lengthened the figure on the left in the final version (bottom) and took away her breast. She has become male.

The only known reference in the two images are the almost-touching hands from Michelangelo's Creation of Adam. Both arms, though, like those in the Creation also represent the outstretched arm of a painter with the man's hand enlarged and floppy like a brush.

Dance (I)

Dance (I) Artist Henri Matisse Year 1909 Catalogue 79124 Medium Oil on canvas Dimensions 259.7 cm × 390.1 cm (102.2 in × 153.6 in) Location Museum of Modern Art, New York City Accession 201.1963 In March 1909, Matisse painted a preliminary version of this work, known as Dance (I). It was a compositional study and uses paler colors and less detail. The painting was highly regarded by the artist who once called it "the overpowering climax of luminosity"; it is also featured in the background of Matisse's Nasturtiums with the Painting "Dance I", (1912). It was donated by Nelson A. Rockefeller in honor of Alfred H. Barr Jr. to the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Dance is a large decorative panel, painted with a companion piece, Music, specifically for the Russian businessman and art collector Sergei Shchukin, with whom Matisse had a long association. Until the October Revolution of 1917, this painting hung together with Music on the staircase of Shchukin's Moscow mansion. The painting shows five dancing figures, painted in a strong red, set against a very simplified green landscape and deep blue sky. It reflects Matisse's incipient fascination with primitive art, and uses a classic Fauvist color palette: the intense warm colors against the cool blue-green background and the rhythmical succession of dancing nudes convey the feelings of emotional liberation and hedonism. The painting is often associated with the "Dance of the Young Girls" from Igor Stravinsky's famous 1913 musical work The Rite of Spring. The composition or arrangement of dancing figures is reminiscent of Blake's watercolour "Oberon, Titania and Puck with fairies dancing" from 1786.[6] Dance is commonly recognized as "a key point of (Matisse's) career and in the development of modern painting".[7] It resides in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. It was loaned to H'ART Museum for a period of six weeks from April 1 to May 9, 2010.

Perhaps inspired by a similar illusion in Michelangelo's Last Judgment, also in the Sistine Chapel, Matisse's self-caricature in Dance II is drawn like the ones he so often added to postcards and letters home (right).

The figure's breasts become his glasses and thereby represent creative fertility while the contour of her rib-cage is the artist's nose, its nostril a line of shadow below.

Matisse, though, could define his face by glasses and beard alone, the latter seen in the curved lines of her voluminous abdomen.

The Dance II

The Dance by Henri Matisse is a triptych mural (15 ft high by 45 ft long) in the Barnes Foundation. It was created in 1932[1] at the request of Albert C. Barnes after he met Matisse in the United States. Barnes was an art enthusiast and long-time collector of Matisse's works, and agreed to pay Matisse a total of $30,000 for the mural, which was expected to take a year.[2] The mural was to be placed above three arches spanning the windows of the main hall of Barnes' gallery. In Nice, France, Matisse executed the mural on canvas provided by Barnes, as opposed to working on site. This was an unusual approach for such a work, but the patron had offered him complete artistic freedom, and working onsite would in any event have been impractical. For Matisse, the project proved to be beset with difficulties, and would end up taking him two years, leaving him physically and emotionally drained. He was also profoundly disappointed to be told on installation that Barnes had no intention of exhibiting the work to the public.[3] Nevertheless, Matisse was delighted with the work itself. In a 1933 letter to his son, Matisse wrote about the installation at the Barnes Foundation: "It has a splendour that one can't imagine unless one sees it -- because both the whole ceiling and its arched vaults come alive through radiation and the main effect continues right down to the floor...I am profoundly tired but very pleased. When I saw the canvas put in place, it was detached from me and became part of the building."[2] Some commentators consider that The Dance mural was pivotal in enabling Matisse to return to the most essential sources of his art.[2][4] For Matisse, the work highlighted aspects such as simplicity, flattening, the emphasis on colour and the use of paper cut-outs which would all go on to play an important role in his later artistic development.[5]